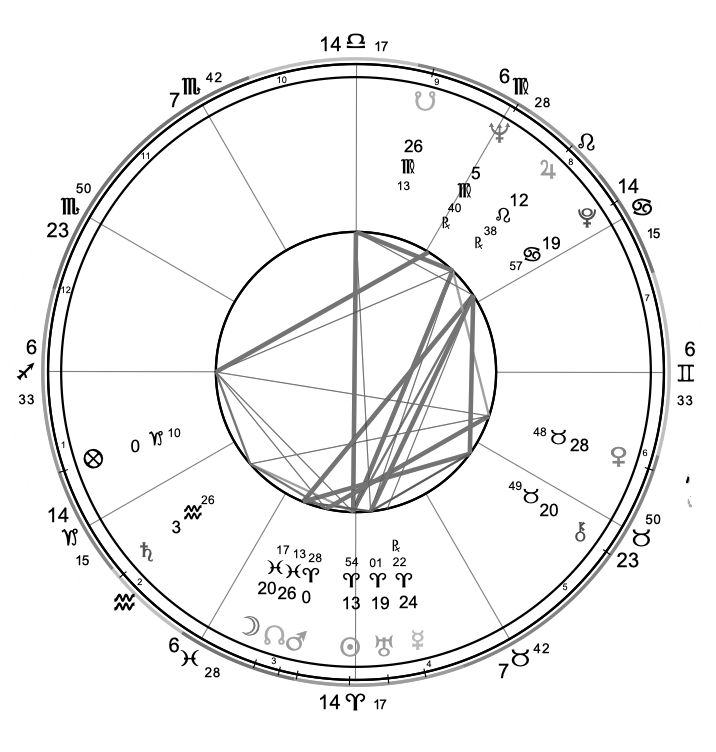

Tarkovsky

owed much to his heredity. He was

born in 1932 into the Moscow

intelligentsia. His father, Arseny, was a respected

poet, while his mother, Maria, was a talented actress and an editor.

As a teenager, Tarkovsky held his father

in high regard, so much so that his parents’ separation evoked a deep

crisis in Tarkovsky and his younger sister, a crisis he later explored in his

films.

Much has been made of

the feminine sensibility that influenced Tarkovsky as a child. Tarkovsky’s mother and grandmother

continuously sought to instill a love and vocation for the arts and the

intellect in the children. His mother, in particular, had high cultural

ambitions for him. Young Andrei resented this and caused his mother a lot of worries.

Despite his rebelliousness, he loved books and was only quiet when reading 4.

“Learn to love solitude, to be more alone with yourself. The

individual must learn to be on his own as a child. Getting bored with oneself

is a very dangerous symptom, almost a disease.”

His mother’s persistent attempt

to foster in him a sense that he was an artist-in-waiting ultimately paid off. Now

in his twenties, Tarkovsky saw himself as a dandy, a contemporary Dostoyevsky

with a boundless, antimodern modernist aesthetic preference 5.

His belief in

miracles, flying saucers, and extra-terrestrial harmoniously combined with his

faith in God 6. He knew the Gospels of St. Matthew and St. Luke practically

by heart and could quote whole paragraphs.

"Art, as a spiritual action,

is very much bound up with certain inner religiousness. Our soul, our existence,

our way of existing is linked with art, and that is bound to show in our works.

The manner of

thinking and the manner of expression always convey some inner spiritual state.

"

With great

pleasure, he admired progressive and exciting minds. He honoured Dovzhenko,

Bresson, Antonioni, Fellini, Vigo, and Paradzhanov, for they knew how to conjure

the spirit of abundance in their creations: “they had the ability to love

the beauty and be completely free inside their own creation.” Those film poets

he promoted to the sky.

Throughout Tarkovsky's seven feature films, from Ivan's

Childhood (1962) to The Sacrifice (1986), Tarkovsky makes every detail of his inner universe visible to society. His use of Bach, childhood

memories, the poems of his father, and artistic introspection reveal a unique look

into his life and culture, daringly expressing

that which lies beyond silence 7.

Cinema, of course, brings stories to life. However, Tarkovsky’s aim was

not to put across a few good stories but to send a universal message and

stimulate reflection on what is essentially human and eternal in each Soul. This

refers to the root

of our mutual recognition. Our lives, separated only in appearance, had been,

deep down, lived together.

Every one of his

creative acts was deliberately puzzling. He wanted the viewer to build an idea

of the rest and develop a connection with his characters on a level other than words, in mind, in the subconscious: "it

isn't a question of details, but of what is hidden."

Nature,

the pantheistic Goddess, appealed to him deeply 8. She, as it seems,

forces herself through the screen and flows as the central theme in all of Tarkovsky’s work.

As a

transformative element, Fire in his films is present in the form of candles,

bonfires, self-immolation, buildings ablaze, and flares. The element of Fire is

often seen as something that purifies but also destroys. As a creative

force, Tarkovsky felt the most kinship with the element of Water:

"water is very important, it is alive, it has

depth, it moves, it changes, it reflects like a mirror" 9 10 .

The element of the Earth

acts as a unifier and appears mainly in the form of mud, firmly reminding his

characters that they are inherently earthbound and in unity with Gaia and that

on

this

Earth, their destinies must be found and lived out. Air, as a

communicator, is perhaps the most numinous element for Tarkovsky; it usually

occurs in the form of sudden winds that blow up, most memorably in Mirror and

Stalker.

Tarkovsky, working in communion with the great alchemical laboratory of Nature, coaxes

humanity toward higher consciousness. Habits of feeling (Water), thinking (Air), acting (Fire), and

relating to the material world (Earth) are actual states from which the

material universe emerges.

“My films are

not a personal expression but a prayer. When I make a film, it's like a holy

day. As if I were lighting a candle in front of an icon or placing a bouquet of

flowers before it.” 11

Much more could be written

about Tarkovsky and his cinematographic poetry of the beautiful, but for now, I

leave his flowing poetic scenes to make a connection with you. There

is something very intimate and personal about his seemingly transcendent

films that can only be understood by those

submerged in the experience of the great unknown and unknowable, the divine,

the spiritual, and the indecipherable.